[Note] This article by Matt Jone is from 2009, but like much writing about the nature of cities, has a timeless quality. Cities are like timewarps, each street seeming to hold on to its heyday regardless of when it was. I was drawn to it because it explores the image of the city of the future as presented in science fiction, a realm of mind unrestrained by urban design and necessarily reflecting an imagined culture derived from circumstances of that authors’s time- their very own timewarp. It is an interesting take of the City of the Future.

The architecture of science fiction has profoundly changed urban design. When building cities of the future, our best guides may be places like comic book megalopolises Mega-City-1 or Transmet.

In February of this year I gave a talk at webstock in New Zealand, entitled “The Demon-Haunted World” – which investigated past visions of future cities in order to reflect upon work being done currently in the field of ‘urban computing’.

In particular I examined the radical work of influential 60’s architecture collective Archigram, who I found through my research had coined the term ‘social software’ back in 1972, 30 years before it was on the lips of Clay Shirky and other internet gurus.

Rather than building, Archigram were perhaps proto-bloggers – publishing a sought-after ‘magazine’ of images, collage, essays and provocations regularly through the 60s which had an enormous impact on architecture and design around the world, right through to the present day. Archigram have featured before on io9, and I’m sure they will again.

They referenced comics – American superhero aesthetics but also the stiff-upper-lips and cut-away precision engineering of Frank Hampson’s Dan Dare and Eagle, alongside pop-music, psychedelia, computing and pulp sci-fi and put it in a blender with a healthy dollop of Brit-eccentricity. They are perhaps most familiar from science-fictional images like their Walking City project, but at the centre of their work was a concern with cities as systems, reflecting the contemporary vogue for cybernetics and belief in automation.

Although Archigram didn’t build their visions, other architects brought aspects of them into the world. Echoes of their “Plug-in city” can undoubtedly be seen in Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ Pompidou Centre in Paris. Much of the ‘hi-tech’ style of architecture (chiefly executed by British architects such as Rogers, Norman Foster and Nicholas Grimshaw) popular for corporate HQs and arts centers through the 80s and 90s can be traced back to, if not Archigram, then the same set of pop sci-fi influences that a generation of british schoolboys grew up with – into world-class architects.

Lord Rogers, as he now is, has made a second career of writing and lobbying about the future of cities worldwide. His books “Cities for a small planet” and “Cities for a small country” were based on work his architecture and urban-design practice did during the 80s and 90s, consulting on citymaking and redevelopment with national and regional governments. His work for Shanghai is heavily featured in ‘small planet’ – a plan that proposed the creation of an ecotopian mega city. This was thwarted, but he continues to campaign for renewed approaches to urban living.

Last year I saw him give a talk in London where he described the near-future of cities as one increasingly influenced by telecommunications and technology. He stated that “our cities are increasingly linked and learning” – this seemed to me a recapitulation of Archigram’s strategies, playing out not through giant walking cities but smaller, bottom-up technological interventions. The infrastructures we assemble and carry with us through the city – mobile phones, wireless nodes, computing power, sensor platforms are changing how we interact with it and how it interacts with other places on the planet. After all it was Archigram who said “people are walking architecture.”Dan Hill (a consultant on how digital technology is changing cities for global engineering group Arup) in his epic blog post “The Street as Platform” says, “…the way the street feels may soon be defined by what cannot be seen by the naked eye.”

He goes on to explain:

We can’t see how the street is immersed in a twitching, pulsing cloud of data. This is over and above the well-established electromagnetic radiation, crackles of static, radio waves conveying radio and television broadcasts in digital and analogue forms, police voice traffic. This is a new kind of data, collective and individual, aggregated and discrete, open and closed, constantly logging impossibly detailed patterns of behaviour. The behaviour of the street.

Adam Greenfield, a design director at Nokia, wrote one of the defining texts on the design and use of ubiquitous computing or ‘ubicomp’ called “Everyware” and is about to release a follow-up on urban environments and technology called “The city is here for you to use”. In a recent talk he framed a number of ways in which the access to data about your surroundings that Hill describes will change our attitude towards the city. He posits that we will move from a city we browser and wander to a ‘searchable, query-able’ city that we can not only read, but write-to as a medium.

He states:

The bottom-line is a city that responds to the behaviour of its users in something close to real-time, and in turn begins to shape that behaviour.

The city of the future increases its role as an actor in our lives, affecting our lives. This of course, is a recurrent theme in science-fiction and fantasy. In movies, it’s hard to get past the paradigm-defining dystopic backdrop of the city in Bladerunner, or the fin-de-siècle late-capitalism cage of the nameless, anonymous, bounded city of the Matrix. Perhaps more resonant of the future described by Greenfield is the ever-changing stage-set of Alex Proyas’ Dark City.

For some of the greatest-city-as-actor stories though, it’s perhaps no suprise that we have to turn to comics as Archigram did – and the eponymous city of Warren Ellis and Darick Robertson’s Transmetropolitan as documented and half-destroyed by gonzo future journalist-messiah Spider Jerusalem.

Transmet’s city binds together perfectly a number of future-city fiction’s favourite themes: overwhelming size (reminiscent of the BAMA, or “Boston-Atlanta Metropolitan Axis from William Gibson’s “Sprawl” trilogy), patchworks of ‘cultural reservations’ (Stephenson’s Snowcrashwith it’s three-ring-binder-governed, franchise-run-statelets) and a constant unrelenting future-shock as everyday as the weather… For which we can look to the comics-futrue-city grand-daddy of them all: Mega-City-1.

Ah – The Big Meg, where at any moment on the mile-high Zipstrips you might be flattened by a rogue Boinger, set-upon by a Futsie and thrown down onto the skedways far below, offered an illicit bag of umpty-candy or stookie-glands and find yourself instantly at the mercy of the Judges. If you grew up on 2000AD like me, then your mind is probably now filled with a vivid picture of the biggest, toughest, weirdest future city there’s ever been.

This is a future city that has been lovingly-detailed, weekly, for over three decades years, as artist Matt Brooker (who goes by the psuedonym D’Israeli) points out:

Working on Lowlife, with its Mega-City One setting freed from the presence of Judge Dredd, I found myself thinking about the city and its place in the Dredd/2000AD franchise. And it occurred to me that, really, the city is the actual star of Judge Dredd. I mean, Dredd himself is a man of limited attributes and predictable reactions. His value is giving us a fixed point, a window through which to explore the endless fountain of new phenomena that is the Mega-City. It’s the Mega-City that powers Judge Dredd, and Judge Dredd that has powered 2000AD for the last 30 years.

Brooker, from his keen-eyed-viewpoint as someone currently illustrating MC-1, examines the differing visions that artists like Carlos Ezquerra and Mike McMahon have brought to the city over the years in a wonderful blog post which I heartily recommend you read.

Were Mega-City One’s creators influenced by Archigram or other radical architects?

I’d venture a “yes” on that. Mike McMahon, seen to many including Brooker and myself, as one of the definitive portrayals of The Big Meg renders the giant, town-within-a-city Blocks as “pepperpots” organic forms reminiscent of Ken Yeang (pictured below), or (former Rogers-collaborator) Renzo Piano’s “green skyscrapers”.

While I’m unsure of the claim that MC-1 can trace it’s lineage back to radical 60’s architecture, it seems that the influence flowing the other direction, from comicbook to architect, is far clearer. Here in the UK, the Architect’s Journal went as far as to name it the number one comic book city.

Echoing Brooker’s thoughts, they exclaim:

Mega City One is the ultimate comic book city: bigger, badder, and more spectacular than its rivals. It’s underlying design principle is simple – exaggeration – which actually lends it a coherence and character unlike any other. While Batman’s Gotham City and Superman’s Metropolis largely reflect the character of the superheroes who inhabit them (Gotham is grim, Metropolis shines) Mega City One presents an exuberant, absurd foil to Dredd’s rigid, monotonous outlook.

But, these are but speedbumps on the road to the future city.

There are still ongoing efforts to create planned, model future cities such as one that Nick Durrant of design consultancy Plot is working on in Abu Dhabi: Masdar City. It’s designed by another alumni of the British Hi-tech school – Sir Norman Foster. “Zero waste, carbon neutral, car free” is the slogan, and a close eye is being kept on it as a test-bed for clean-tech in cities.

We are now a predominantly urban species, with over 50% of humanity living in a city. The overwhelming majority of these are not old post-industrial world cities such as London or New York, but large chaotic sprawls of the industrialising world such as the “maximum cities” of Mumbai or Guangzhou. Here the infrastructures are layered, ad-hoc, adaptive and personal – people there really are walking architecture, as Archigram said.

Hacking post-industrial cities is becoming a necessity also. The “shrinking cities” project is monitoring the trend in the west toward dwindling futures for cities such as Detroit and Liverpool.

They claim:

In the 21st century, the historically unique epoch of growth that began with industrialization 200 years ago will come to an end. In particular, climate change, dwindling fossil sources of energy, demographic aging, and rationalization in the service industry will lead to new forms of urban shrinking and a marked increase in the number of shrinking cities.

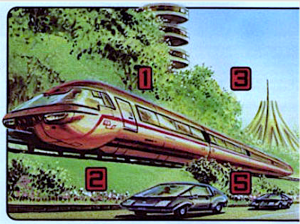

This scene, though not pretending to show that a perfect world is possible nevertheless indicates that tomorrow’s town could be pleasant places to live, work and play in.

1 Electric monorail train provides an effective though not especially elegant solution to the problem of hight speed travel

2 below the line runs a pipe network throudht which most bulk cargo (such as fuel, water,grain) is piped, silently and efficiently.

3 The city is green all over, the result of a massive tree planting scheme stated in the 1950s. It is estimated by present day researchers that every man woman and child on Earth meeds to plant tree a day in order to keep a balance with those that are removed or kill. The worlds main oxygen producing area is, at present, the Brazilian rain forest. This is being chopped down slowly but surely. A balance must be kept

4 Non-polluting yet lowered by hydrogen fuel whose wasted is water flies quietly across the sky

5 Fumeless electric vehicles weed for local travel, Trucks are only needed for short distance hauls as pipe system carry most cargo

6 The worst excesses of mid 20th century ‘brutalist’ architecture are camouflaged with flowering vines

7 Bicycles provide the basic means of transport for people to bet about over short distances. Special bikeways like this keep cyclist apart from truck and cars.

However, I’m optimistic about the future of cities. I’d contend cities are not just engines of invention in stories, they themselves are powerful engines of culture and re-invention.

David Byrne in the WSJ, as quoted by entrepreneur and co-founder of Flickr Caterina Fake, on her blog recently:

A city can’t be too small. Size guarantees anonymity-if you make an embarrassing mistake in a large city, and it’s not on the cover of the Post, you can probably try again. The generous attitude towards failure that big cities afford is invaluable-it’s how things get created. In a small town everyone knows about your failures, so you are more careful about what you might attempt.

Patron saint of cities, Jane Jacobs, in her book “The Economy of Cities” put forward the ‘engines of invention’ argument in her theory of ‘import replacement’:

…when a city begins to locally produce goods which it formerly imported, e.g., Tokyo bicycle factories replacing Tokyo bicycle importers in the 1800s.

Urban computing and gaming specialist, founder of Area/Code and ITP professor Kevin Slavin showed me a presentation by architect Dan Pitera about the scale and future of Detroit, and associated scenarios by city planners that would see the shrinking city deliberately intensify – creating urban farming zones from derelict areas so that it can feed itself locally. Import replacement writ large.

He also told me that 400 cities worldwide independently of their ‘host country’ agreed to follow the Kyoto protocol. Cities are entities that network outside of nations as their wealth often exceeds that of the rest of the nation put together – it’s natural they solve transnational, global problems.

Which leads me back to science-fiction. Warren Ellis created a character called Jack Hawksmoor in his superhero comic series The Authority.

The surname is a nice nod toward psychogeography and city-fans: Hawksmoor was an architect and progeny of Sir Christopher Wren, fictionalised into a murderous semi-mystical figure who shaped the city into a giant magical apparatus by Peter Ackroyd in an eponymous novel.

Ellis’ Hawksmoor, however, was abducted multiple times, seemingly by aliens, and surgically adapted to be ultimately suited to live in cities – they speak to him and he gains nourishment from them. If you’ll excuse the spoiler, the zenith of Hawksmoor’s adventures with cities come when he finds the purpose behind the modifications – he was not altered by aliens but by future humans in order to defend the early 21st century against a time-travelling 73rd century Cleveland gone berserk. Hawksmoor defeats the giant, monstrous sentient city by wrapping himself in Tokyo to form a massive concrete battlesuit.

Cities are the best battlesuits we have.

It seem to me that as we better learn how to design, use and live in cities – we all have a future.

Matt Jones is design director at Berg in London. He has worked as a designer for the BBC and Nokia. He began his career studying architecture, and writes a blog called Magical Nihilism.

https://io9.gizmodo.com/5362912/the-city-is-a-battlesuit-for-surviving-the-future